Mortar

Mortar has been fundamental to masonry construction for millennia. The ancient Egyptians used gypsum mortars, while Roman, Greek, and Phoenician builders developed sand–lime mortars of varying strength and permeability, often enhanced with pozzolanic additives. In contrast, Inca masonry relied on precisely cut stone with little or no mortar.

In Scotland, recent research has shown that clay mortars were widely used prior to 1800, particularly in vernacular construction. Clay was locally available and easily processed, typically soaked and worked into a smooth paste before mixing with sand, and occasionally modified with small quantities of air lime. These mortars were robust, flexible, permeable, and thermally insulating. Emerging evidence suggests that many structures now regarded as “dry stone” may originally have contained clay mortar that has since weathered from the joints. Clay mortars were, however, unsuitable for use at or below the waterline.

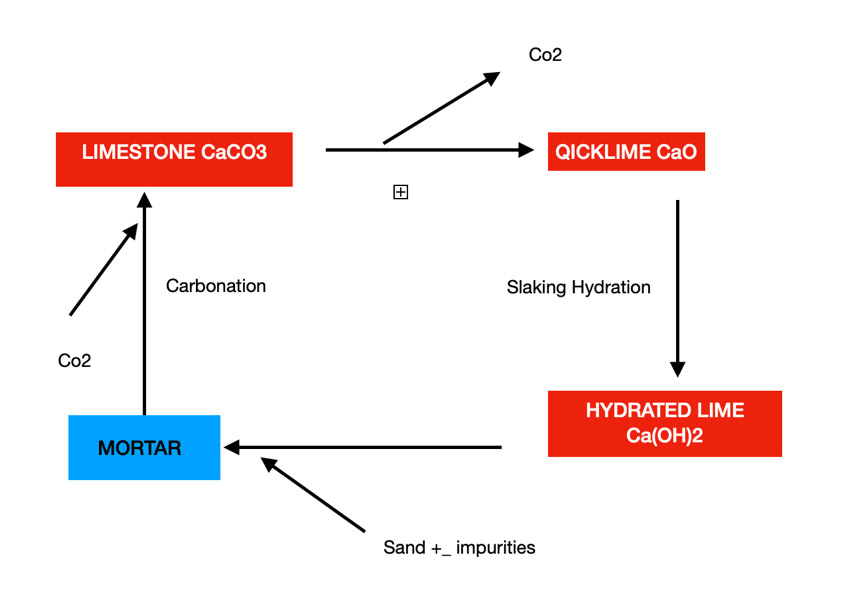

Lime mortars in Scotland are more commonly associated with “polite” architecture and bridge construction. Lime production involved calcining (roasting) limestone or chalk to produce quicklime, which was then slaked either to form dry hydrate, lime putty, or—commonly in Scotland—mixed hot on site with sand and water ( hot-liming). The resulting mortar hardened slowly through carbonation, producing a relatively weak, but flexible and porous material.

In contrast, hydraulic limes are harder and more waterproof. They contain natural silicate impurities that impart greater strength and durability, and in some cases can even set underwater. Natural Hydraulic Limes (NHLs) emerge from impurities in the limestone itself. An alternative pathway is for fully slaked air limes to be 'gauged' with pozzolanic additives, which set through chemical reactions with water rather than atmospheric carbonation. These technologies, developed in antiquity, result in a calcium silicate hydrate gel, which, combined with calcium hydroxide and sand, form a complex but strong, impermeable, non-porous. set. Silicate hydrate compound is also the key ingredient of Portland cement.

Historically, mortar production was a skilled craft, with mixes adjusted empirically to suit specific materials, environments, and structural demands. Analysis of surviving Scottish mortars indicates that up to 75 per cent of pre-1800 examples were clay-based, with or without lime additives. A smaller proportion were pure hydrated or hydraulic lime with sand. Pozzolanic additives and organic inclusions appear to have been less common in Scotland, though natural hydraulic limes would have been indispensable in bridge construction.

Modern conservation practice emphasises that mortar should be weaker and more permeable than the masonry it binds, allowing it to act as a sacrificial and flexible element. Hard, dense, and vapour-impermeable materials—particularly Portland cement and highly hydraulic mortars—can accelerate stone decay and are generally inappropriate for historic masonry. Achieving an appropriate balance between strength, flexibility, and permeability is therefore essential, especially in exposed or water-bearing structures.

Page last updated Dec. '25